Michael Schwerner

Michael "Mickey" Schwerner | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Schwerner | |

| Born | Michael Henry Schwerner November 6, 1939 Pelham, New York, U.S. |

| Died | June 21, 1964 (aged 24) |

| Cause of death | Murder |

| Other names | Mickey Schwerner |

| Spouse | |

| Awards | Presidential Medal of Freedom (Posthumous; 2014) |

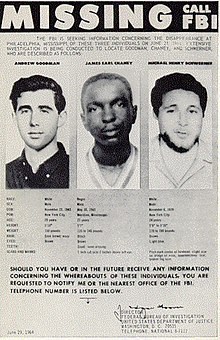

Michael Henry Schwerner (November 6, 1939 – June 21, 1964) was an American civil rights activist. He was one of three Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) field workers killed in rural Neshoba County, Mississippi, by members of the Ku Klux Klan. Schwerner and two co-workers, James Chaney and Andrew Goodman, were killed in response to their civil rights work, which included promoting voting registration among African Americans, most of whom had been disenfranchised in the state since 1890.

Early life and education

[edit]Born and raised in Pelham, New York,[1][2] to a family of Jewish heritage, Schwerner attended Pelham Memorial High School. He was called Mickey by his friends. His mother, Anne Siegel (May 1, 1912 – November 29, 1996), was a science teacher at nearby New Rochelle High School, and his father, Nathan Schwerner (June 19, 1909 – March 6, 1991), was a businessman. Schwerner attended Michigan State University, originally intending to become a veterinarian. He transferred to Cornell University and switched his major to rural sociology.[3] While an undergraduate at Cornell, he was initiated into the school's chapter of Alpha Epsilon Pi fraternity. He entered graduate school at the School of Social Work at Columbia University.

As a boy, Schwerner befriended Robert Reich, who later became U.S. Secretary of Labor. Schwerner helped protect Reich, who was smaller, from bullies.[4][5]

Civil rights activism

[edit]In the early 1960s Schwerner became active in working for civil rights for African Americans; he led a local Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) group on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, called "Downtown CORE." He participated in a 1963 effort to desegregate Gwynn Oak Amusement Park in Maryland. As activism increased in the South, Schwerner, recruited by John Lewis,[6] and his wife, Rita Schwerner Bender, volunteered to work for National CORE in Mississippi, under the tutelage of Dave Dennis, the CORE state director. Bob Moses assigned the Schwerners to organize the community center and activities in Meridian. James Chaney was a local youth who started working with them there. The Schwerners were the first whites to be assigned by CORE permanently outside the state capital of Jackson. In the summer of 1964 CORE intended to hold classes and drives to register African Americans to vote in the state, what they called "Freedom Summer". Many volunteers, mostly college students and young adults, had been recruited from local communities and northern/western states to work on this project.

Civil rights activists were resented and held under suspicion by white Mississippians. Spies paid by the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, a taxpayer-funded agency, kept track of all northerners and suspected activists. The Commission conducted economic boycotts and intimidation against activists. In 1998 its records were opened by court order, revealing the state's deep complicity in the 1964 murders of three civil right workers because its investigator, A. L. Hopkins, passed on information about the workers, including their car license number, to the Commission. Records showed the Commission passed the information on to the Sheriff of Neshoba County, Lawrence Rainey, who was implicated in the murders.[7]

The Ku Klux Klan targeted Schwerner after he and his wife, Rita, had taken over the Meridian CORE field office, where they established a community center for blacks as part of grassroots organizing. Schwerner tried to establish contact with white working-class citizens of Meridian and went door-to-door to speak with them. He also organized a black boycott of a popular variety store until it hired its first African American, under the principle of "don't shop where you can't work".

Murder

[edit]

James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner were murdered near the town of Philadelphia, Mississippi. They were investigating the burning of Mt. Zion Methodist Church, which had been a site of a CORE Freedom School, in a nearby community. Parishioners had been beaten in the wake of Schwerner and Chaney's voter registration rallies for CORE. The Sheriff's Deputy, Cecil Price, had been accused by parishioners of stopping their caravan and forcing the deacons to kneel in the headlights of their own cars, while they were beaten with rifle butts. That same group of white men was identified as having burned the church.

Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price arrested Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner for an alleged traffic violation and took them to the jail in Neshoba County. They were released that evening, without being allowed to telephone anyone. On the way back to Meridian, they were stopped by patrol lights and two carloads with members of the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan on Highway 19, then taken in Price's car to another remote rural road. One of the Klansmen, Alton Wayne Roberts, reportedly pulled Schwerner out of the car, pointed a gun at his chest, and asked "Are you that nigger lover?". Schwerner replied "Sir, I know just how you feel," before Roberts shot him in the heart. Goodman was killed by Roberts in the same manner, while Chaney was killed by either Roberts or James Jordan, after beating, chain-whipping and castrating him.

The men's bodies remained undiscovered for 44 days. In the meantime, the case of the missing civil-rights workers became a major national story, especially coming on top of other events during Freedom Summer. The federal government quickly assigned the FBI to a full investigation and called in Navy sailors and other forces to aid in the search.

Schwerner's widow Rita, who also worked for CORE in Meridian, expressed indignation publicly at the way the story was handled. She said she believed that if only Chaney (who was black) was missing and the two white men from New York had not been killed along with him, the case would not have received nearly as much national attention, as other black civil rights workers had earlier been killed in the South.[8]

First trial

[edit]The US government prosecuted the case under the Enforcement Act of 1870. Seven men, including Deputy Sheriff Price, were convicted. Three strongly implicated defendants were acquitted because of a jury deadlock.

Reinvestigation

[edit]

Journalist Jerry Mitchell, an award-winning investigative reporter for the Jackson Clarion-Ledger had written extensively about the case for many years in the late 20th century. Mitchell had earned renown for helping secure convictions by his investigation of several other high-profile Civil Rights Era murder cases, including the assassination of Medgar Evers in Mississippi, the 1963 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, and the murder of Vernon Dahmer in his Mississippi home, the latter of which was ordered by Samuel Bowers, founder of the Klan chapter that killed the CORE activists. Mitchell developed new evidence, found new witnesses, and pressured the state to take action. Barry Bradford, an Illinois high school teacher, and three students: Allison Nichols, Sarah Siegel, and Brittany Saltiel, joined Mitchell's efforts. Their documentary, produced for the National History Day contest, presented important new evidence and compelling reasons for reopening the case. Bradford also obtained an interview with Edgar Ray Killen, which helped convince the State to reinvestigate. Mitchell was able to determine the identity of "Mr. X",[9] the mystery informer who had helped the FBI discover the bodies and smash the conspiracy of the Klan in 1964. He relied in part on evidence developed by Bradford.

On January 7, 2005, Edgar Ray Killen, an outspoken white supremacist nicknamed "Preacher," pleaded "Not Guilty" to state charges of the murders of the three men. The jury found him guilty of three counts of manslaughter on June 21, 2005. He was the only man charged with homicide in connection to the killings. Killen was sentenced to sixty years in prison—twenty years for each count, served consecutively. Killen passed away in prison in 2018, aged 92.

Personality

[edit]Schwerner "was described by family and friends as friendly, good-natured, gentle, mischievous, and 'full of life and ideas'. He believed all people were essentially good. He loved sports, animals, poker, W.C. Fields, and rock music."[10]

Robert Reich, the American political commentator, professor, and author who served in the administrations of Presidents Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, and Bill Clinton, says that as a child, he was bullied, and sought out the protection of older boys; one of them was Michael Schwerner. Reich cites this event as an inspiration to "fight the bullies, to protect the powerless, to make sure that the people without a voice have a voice."[11]

Legacy and honors

[edit]

Schwerner

[edit]- In 2008, his hometown of Pelham, New York, renamed a section of Harmon Avenue as "Michael Schwerner Way" in his honor.[2][12]

- Schwerner, along with Goodman and Chaney, received a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama in 2014.[13]

In popular culture

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "1964: Three civil rights activists found dead". BBC News. August 4, 1964. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- ^ a b "Activist Michael Schwerner, PMHS grad murdered by Klan in '64, memorialized with plaque near street named for him". Pelham Examiner. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- ^ "The Cornell Daily Sun 23 September 1964". cdsun.library.cornell.edu.

- ^ Patrick Gavin (July 30, 2012). "Answer This: Robert Reich". Politico. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ Robert Reich (September 26, 2023). "When the Klan murdered my protector". Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ^ Stolberg, Sheryl Gay (July 23, 2020). "The Blessing and Burden of Being John Lewis". The New York Times. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- ^ AP (March 18, 1998). "Mississippi Commission's Files a Treasure Trove of Innuendo". MDCBowen.org. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- ^ Neshoba (2008) documentary film

- ^ "Mississippi Burning FAQs - Speaking For A Change". May 31, 2012.

- ^ "Biography of Michael Schwerner". University of Missouri-Kansas City Law School. Archived from the original on May 15, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ Robert Reich (November 18, 2011). "Transcript: Robert Reich’s speech at Occupy Cal". The Daily Californian. Retrieved September 11, 2013. http://www.dailycal.org/2011/11/18/transcript-robert-reichs-speech-at/

- ^ "Section of Harmon Avenue Dedicated as "Michael Schwerner Way"". The Pelhams-PLUS. June 13, 2008. Archived from the original on June 30, 2013. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- ^ "President Obama Names Recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom". whitehouse.gov. November 10, 2014 – via National Archives.

External links

[edit]- “Long, Hot Summer '64; Episode 9,” 1964-08-06, WGBH, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC, accessed June 7, 2021.

- The True Story Of How The Mississippi Burning Case Was Reopened

- Biography of Michael Schwerner Archived May 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine from University of Missouri–Kansas City Law School

- 1939 births

- 1964 deaths

- 1964 murders in the United States

- 20th-century American people

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- American murder victims

- American people of Jewish descent

- Assassinated American civil rights activists

- Cornell University alumni

- Columbia University School of Social Work alumni

- Deaths by firearm in Mississippi

- Jewish civil rights activists

- Murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner

- Michigan State University alumni

- Murdered American Jews

- People from Pelham, New York

- People from the Bronx

- People murdered in Mississippi

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Victims of the Ku Klux Klan

- People murdered by law enforcement officers in the United States