James Farley

James Farley | |

|---|---|

| |

| 50th United States Postmaster General | |

| In office March 4, 1933 – September 10, 1940 | |

| President | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | Walter Folger Brown |

| Succeeded by | Frank C. Walker |

| Chair of the Democratic National Committee | |

| In office July 2, 1932 – August 17, 1940 | |

| Preceded by | John J. Raskob |

| Succeeded by | Edward J. Flynn |

| Chair of the New York Democratic Party | |

| In office October 1930 – June 1944 | |

| Preceded by | M. William Bray |

| Succeeded by | Paul Fitzpatrick |

| Member of the New York Assembly from Rockland County | |

| In office January 1, 1923 – December 31, 1923 | |

| Preceded by | Pierre DePew |

| Succeeded by | Walter Gedney |

| Personal details | |

| Born | James Aloysius Farley May 30, 1888 Grassy Point, New York, U.S. |

| Died | June 9, 1976 (aged 88) New York City, U.S. |

| Resting place | Gate of Heaven Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Elizabeth Finnegan

(m. 1920; died 1955) |

| Children | 3 |

| Education | Packard Business College |

James Aloysius Farley (May 30, 1888 – June 9, 1976) was an American politician who simultaneously served as chairman of the New York State Democratic Committee, chairman of the Democratic National Committee, and Postmaster General under President Franklin Roosevelt, whose gubernatorial and presidential campaigns were run by Farley.

Born and raised in Rockland County, New York, Farley entered politics at a young age and quickly rose to run the Rockland County Democratic Party. After short stints campaigning for governor Al Smith and serving in the state legislature, he befriended Roosevelt and worked to build an effective Democratic machine across the entire state. Following Roosevelt's victories in the gubernatorial elections of 1928 and 1930, he ran Roosevelt's 1932 and 1936 presidential campaigns. His campaign style was meticulous and involved massive amounts of correspondence with individual party members to gather information and coordinate strategy. The 1936 campaign, where he correctly predicted the outcome in every state, earned him particular recognition.

Working as the chairman of the Democratic national committee and postmaster general, Farley worked to settle factional disputes within the party during Roosevelt's first term, using his massive network of personal connections and patronage. Farley found himself in a transitional period in party politics, as Roosevelt and the New Deal coalition moved from a traditional party system built on local organizations and patronage to a national party system where parties campaigned on specific issues and relied on the support of auxiliary organizations. In Roosevelt's second term, Farley found himself sidelined by Roosevelt, and broke with the president over his attempts to influence Congressional primary elections in favor of pro-New Deal candidates. Farley mounted a failed campaign for president to prevent Roosevelt from winning a third term in 1940.

Following his defeat, Farley was hired by the Coca-Cola Export Corporation, where he worked to promote international sales from 1940 to 1973. He also remained active in New York politics and served on the Hoover Commission from 1953 to 1956.

Early life

[edit]Farley was born on May 30, 1888, in Grassy Point, New York, to James Farley Sr. and Ellen Farley (née Goldrick). All four of his grandparents had immigrated to the United States from Ireland in the 1840s. James Farley Sr. was involved in the brick-making industry, first as a laborer and later as a part-owner of three schooners engaged in the brick-carrying trade.[1]

James Farley Sr. died in an accident with a horse in January 1898. After the sudden death, Farley helped his mother tend a bar and grocery store that she purchased to support the family. After graduating from high school, he attended Packard Business College in New York City to study bookkeeping and other business skills. After his graduation, he was employed by the United States Gypsum Corporation.[2]

Early political career

[edit]Farley made his entry into politics in 1908, working for Alex Sutherland during his unsuccessful campaign to become town clerk of Stony Point. In 1910, Farley ran for the office of town clerk himself and won. Despite Stony Point's Republican leanings, Farley was reelected twice.[3] He was elected chairman of the Rockland County Democratic Party in 1918. That same year, he campaigned for Al Smith to become Governor of New York and befriended many politicians in Tammany Hall, although he would repeatedly fail to enter Smith's inner circle of advisors.[4] Smith appointed Farley to be a Port Warden of New York City between 1918 and 1919.[5] Farley married the former Elizabeth A. Finnegan ("Bess") in April 1920. They had two daughters, Elizabeth and Ann, and one son, James A. Farley Jr.[6]

Farley ran for the New York State Assembly in 1922 and won in Rockland County, normally a solid Republican stronghold. He sat in the 146th New York State Legislature in 1923, where he introduced 33 bills, 19 of which passed.[7] He lost his seat at the next election. Farley blamed the loss on his vote for the repeal of the Mullan–Gage Act, the state law to enforce Prohibition, while other biographers attributed the loss to his associations with Tammany Hall.[8]

Farley was appointed to the New York State Athletic Commission by Governor Smith with the support of Tammany boss Charles F. Murphy and Jimmy Walker. He soon became chairman of the commission and held the title until he joined the Roosevelt administration in 1933.[9] In 1926, Farley threatened to resign his post as Athletic Commissioner if boxing champion Jack Dempsey did not fight the mandatory challenger, African-American fighter Harry Wills. Farley banned Dempsey from fighting Gene Tunney and publicly threatened to revoke Tex Rickard's Madison Square Garden license if he ignored the ruling of the commission. The intervention was popular with African Americans who viewed Dempsey's decision as a form of discrimination.[10] Farley was also accused of purchasing thousands of tickets to boxing matches to give away as favors.[11] During his time on the commission, Farley continued work his business interests. His company merged with five other building contractors to form the General Builders Supply Corporation, which Farley served as president of from 1929 to 1933.[12]

Roosevelt's campaign manager

[edit]

Farley served as a delegate to the 1924 Democratic National Convention, where he befriended Franklin D. Roosevelt, who would give his famous "Happy Warrior" speech for Smith.[13] In 1928, Smith became the Democratic nominee in the presidential election, and Roosevelt ran for governor to replace Smith. Farley was chosen as the secretary for the New York State Democratic Committee that summer, and launched a letter-writing campaign to the state's county organizations to support Roosevelt. Although Smith failed to win New York in the presidential election, Roosevelt was successfully elected governor, due to stronger support in upstate New York.[14]

In 1929, Farley toured the state to gather information on the state of each county party organization, which he compiled in a report to Roosevelt. He recommended that the Democrats involve more women in party affairs to better appeal to women voters and distribute patronage more fairly to the various counties, a principle he labeled "proper consideration". He also encouraged county organizations to replace ineffective chairmen and establish full committees covering every precinct in their counties.[15] Farley replaced William Bray as chairman of the New York Democratic Party in 1930.[16] That year, Roosevelt was reelected with a massive majority, sweeping 42 of the 57 counties in upstate New York.[17]

After the success in 1930, Roosevelt turned his attention to running in the 1932 presidential election. Knowing that Al Smith would compete with him for the northeastern delegates at the Democratic convention, Roosevelt sought the support from other regions. Farley toured the western United States in 1931 to determine the willingness of western Democrats to support Roosevelt, claiming that he was merely traveling to an Elks convention in Seattle, a disguise which fooled few.[18] Although his efforts to build support for Roosevelt among urban machines in the northeast and midwest failed,[19] Farley became familiar with members of the Texas delegation and used his connections to secure Roosevelt's nomination on the fourth ballot at the 1932 Democratic National Convention by offering to make Texan leader John Nance Garner the running mate.[20] For his previous work, Farley was elected chairman of the Democratic National Committee and chosen by Roosevelt to be his campaign manager.[21]

During the 1932 presidential election, Farley befriended Indiana journalist Claude G. Bowers, whom Roosevelt had also recruited to work for the campaign.[22] After Roosevelt's victory, Bowers was appointed as the United States Ambassador to Spain with Farley's recommendation. The two would continue a correspondence during Roosevelt's presidency to keep each other informed on domestic and foreign developments, and Bowers would write many speeches for Farley.[23]

Farley's role as Roosevelt's campaign manager continued in the 1936 presidential election. Ahead of the 1936 Democratic National Convention, Farley lobbied the rest of the party to repeal the convention rule requiring a two-thirds majority for presidential nominees.[24] He continued his systematic approach to campaigning and maintained a massive correspondence list with party officials across the country, monitoring the situation on the ground and providing advice based on his experience in New York.[25] The election marked the high point of Farley's political career when he correctly predicted that Roosevelt would win all but two states, Maine and Vermont.[26]

New Deal

[edit]Following Roosevelt's election as president, Farley was appointed Postmaster General, a cabinet position which oversaw patronage for over 100,000 civil service-exempt jobs.[27] Farley used his position effectively to mediate disputes between different factions during Roosevelt's first term and avoided any major scandals around appointments.[28] However, Farley was frustrated by competition from cabinet secretaries for control of appointments to various New Deal programs, and disagreed with Roosevelt and other cabinet secretaries on who to reward with patronage, believing that partisan loyalty mattered more than ideological alignment with the New Deal.[29] At Roosevelt's direction, Farley did not lend any support to the Tammany machine, now opposed to Roosevelt, in New York City's mayoral election in 1933, enabling Fiorello La Guardia, a Republican who supported the New Deal, to be elected mayor, and did not intervene against the Wisconsin Progressive Party or Minnesota Farmer–Labor Party, both of which supported the New Deal, in the 1934 midterm elections.[30] Some patronage was diverted to progressive Republican Hiram Johnson and to Wisconsin Progressive Robert M. La Follette Jr. over objections from Democrats.[31]

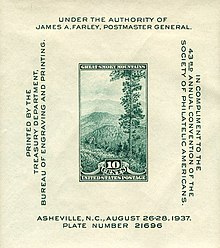

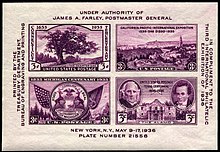

Farley's role is remembered among stamp collectors for two things. One is a series of souvenir sheets that were issued at commemorative events and bore his name as the authorizer. The other is the 20 stamps, known as "Farley's Follies", which were reprints, mostly imperforate and ungummed, of stamps of the period: Farley bought them at face value, out of his own pocket, and gave them to Roosevelt and Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, both collectors, and to members of his family and special friends of the Administration. (Farley himself did not collect stamps.) Unfortunately, some of them reached the market, offered at the high prices commanded by rarities. When ordinary stamp collectors learned of that, they lodged strenuous protests, newspaper editorials leveled charges of corruption, and a heated Congressional investigation ensued. Finally, in 1935 many more of the unfinished stamps were produced and made generally available to collectors at their face value.[34]

During Roosevelt's second term, Farley's close relationship with the president deteriorated. Roosevelt began making decisions without consulting Farley, instead relying on advisors Harry Hopkins and Thomas Corcoran to fill his role, and damaged Farley's relationships with members of Congress by introducing his court-packing plan and intervening in the Senate leadership election following Joseph T. Robinson's death.[35] In 1938, Roosevelt intervened in congressional primaries by endorsing progressive candidates over conservatives, infuriating Farley.[36] A split between the two was rumored in the press that summer.[37]

In 1940 Farley authorized the first postage stamp featuring the likeness of an African American, Booker T. Washington.[38] This effort was spearheaded by Eleanor Roosevelt as well as others. The first Booker T. Washington stamp was sold by Farley to George Washington Carver at the Tuskegee Institute on April 7, 1940.[39] Farley also appeared as a featured speaker at the American Negro Exposition in Chicago in 1940 to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the end of slavery in the United States at the conclusion of the Civil War in 1865.[40]

Presidential candidate

[edit]As the 1940 presidential election approached, Farley joined forces with other Democrats who wished to prevent him from seeking a third term. In January 1939, he compiled a report assessing his own prospects on winning the Democratic nomination and other potential anti-Roosevelt Democrats, and he traveled extensively to determine support for a third term.[41] Farley was at a disadvantage due to his lack of experience in elected office, knowledge of foreign policy, or a defined platform.[42] Roosevelt initially declined to make a formal announcement that he was running for a third term and arranged a meeting between Farley and Cardinal George Mundelein in July 1939 in which Mundelein advised Farley against running for president.[43] Farley traveled to Europe in the summer of 1939, visiting several countries and enjoying an audience with Pope Pius XII, but the outbreak of war in Europe upon his return discouraged him from publicly announcing his presidential candidacy.[44] Farley remained optimistic of his chances as he traveled, believing that he could overcome these issues using the same methods he always had. He took great interest in his ability to meet new voters, to the point that during a tour of the southern states in April 1940, he had someone count how many people he exchanged a handshake with. He managed to shake hands with at least 9,847 voters, and estimated he met another 1,500 which were not counted.[45]

At the 1940 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Farley was nominated for president by his ally Carter Glass. He finished a distant second on the first ballot, with 72+1⁄2 delegates to Roosevelt's 946+1⁄2.[46] Following the defeat, Farley resigned from his positions as national chairman and postmaster general. He confided to Bowers, "I did what I thought was best and I have no apologies and no regrets. My conscience is clear."[47]

Later life

[edit]

After leaving office in 1940, Farley was named chairman of the board of the Coca-Cola Export Corporation.[27] Farley held this post until his retirement in 1973.[48] Roosevelt considered appointing Farley as director of the Relief and Rehabilitation Commission during World War II, but decided against it.[49] In 1943, knowing he would not be allowed to participate in the war effort, Farley moved with Bess to New York City, where he would live in the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel for the remainder of his life. Between 1953 and 1956, he would serve on the Hoover Commission with his Waldorf neighbor, former president Herbert Hoover, although his work for Coca-Cola occupied most of his time.[50]

Farley remained the chairman of the New York Democratic Party after his resignations.[51] In 1941, he was encouraged by allies to run for mayor of New York City. He declined, but supported William O'Dwyer's failed campaign against La Guardia, delivering several speeches accusing La Guardia of being a communist.[52] Farley faced a final political battle with Roosevelt in 1942, when the president intervened to promote a pro-New Deal candidate, James M. Mead, over Attorney General John J. Bennett Jr. Bennett was victorious at the state convention with Farley's help,[53] but this was a Pyrrhic victory, as Bennett's poor relationship with organized labor caused him to lose to Republican Thomas E. Dewey. Farley would resign as chairman on June 8, 1944.[54] After a failed attempt to thwart Roosevelt from seeking a fourth term, Farley largely retired from politics. He would make one final attempt to seek office in 1958 with an abortive campaign to run for the United States Senate seat being vacated by Irving Ives.[55] In 1965, Farley served as the campaign chairman for the failed first Mayoral bid of Abraham Beame, who would go on to be the first practicing Jewish Mayor of New York in 1973.[27]

On November 6, 1947, Farley was the first ever guest to appear on NBC's Meet the Press program.[56]

On October 26, 1963, Tuskegee University conferred upon Farley the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws for his "many contributions to public life"[57] and for his "distinguished possession of the private personal virtues."[58]

Farley was given the Laetare Medal, the oldest and most prestigious award for American Catholics, by the University of Notre Dame, in 1974.[59]

On June 9, 1976, Farley died in his suite at the Waldorf Astoria.[48] The last surviving member of Roosevelt's cabinet, he was interred at the Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Hawthorne, New York.

Legacy

[edit]

Farley was commonly referred to as a political kingmaker for his work on Roosevelt's rise to the presidency.[60] He was renowned as a political prophet for his correct predictions of the outcomes of the 1932 and 1936 presidential elections. Maine's status as a bellwether in national elections had been established since 1888 by the saying "As Maine goes, so goes the nation". Speaking to reporters after the 1936 election, Farley gave the famous remark, "As Maine goes, so goes Vermont".[61][62]

Historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. called Farley the last member of the "classical school" of machine politicians in the Democratic Party, who built political parties around local organizations to win votes. Farley failed to adapt to the New Deal and the introduction of political campaigns based on ideologies and issues, preferring to work as a broker of patronage and services for party members.[63][64] During Farley's time as chairman of the Democratic National Committee, his organizing efforts were frustrated by the emergence of parallel organizations to the party, most notably the Congress of Industrial Organizations, which raised its own funds to support candidates instead of donating directly to the party,[65] and he failed to understand the concepts behind the New Deal Coalition that made the 1936 campaign succeed.[66]

The landmark James A. Farley Building in New York City was named for Farley as a monument to his career in public service.[67]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Scroop 2006, pp. 9–10

- ^ Scroop 2006, pp. 10–12

- ^ Scroop 2006, pp. 15–16

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 17,25

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 21

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 18

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 19

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 20

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 21–22

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 22–23

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 24

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 233

- ^ Scroop 2006, pp. 36–37

- ^ Scroop 2006, pp. 38–40

- ^ Scroop 2006, pp. 41–43

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 47

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 30

- ^ Scroop 2006, pp. 60–61

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 73

- ^ Scroop 2006, pp. 64–65, 71

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 75

- ^ Spencer 1996, pp. 27–28

- ^ Spencer 1996, pp. 29, 31

- ^ Scroop 2006, pp. 128–129

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 125

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 130

- ^ a b c Whitman, Alden (June 10, 1976). "Farley, 'Jim' to Thousands, Was the Master Political Organizer and Salesman". The New York Times. p. 64. Archived from the original on April 3, 2020.

- ^ Scroop 2006, pp. 83, 90

- ^ Scroop 2006, pp. 84–85

- ^ Scroop 2006, pp. 92–95

- ^ Schlesinger 1957, p. 422

- ^ Young & Young 2007, pp. 520–522

- ^ Young & Young 2007, pp. 520–522

- ^ Young & Young 2007, pp. 520–522

- ^ Scroop 2006, pp. 161–162

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 165

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 172

- ^ "Farley Sells First B.T. Washington Stamp and Lauds 'Negro Moses' at Tuskegee". The New York Times. April 8, 1940.

- ^ "Yesterday in Negro History". Jet. Vol. XXIII, no. 25. April 11, 1963.

- ^ Congress, United States (1940). "Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the ... Congress".

- ^ Scroop 2006, pp. 175, 177

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 174

- ^ Scroop 2006, pp. 179–180

- ^ Scroop 2006, pp. 178–179

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 184

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 189

- ^ Spencer 1996, p. 44

- ^ a b "James A. Farley, 88, Dies; Ran Roosevelt Campaigns". The New York Times. June 10, 1976. p. 1. Archived from the original on November 3, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Spencer 1996, p. 44

- ^ Scroop 2006, pp. 220–221

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 200

- ^ Scroop 2006, pp. 202–205

- ^ "The Nation: Farley Wins". Time. August 31, 1942. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ Scroop 2006, pp. 212–213

- ^ Scroop 2006, pp. 217, 221–222

- ^ "James A. Farley: The first guest on 'Meet the Press'". NBC News. Retrieved November 10, 2024.

- ^ Congress, United States (1963). "Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the ... Congress".

- ^ Congress, United States (1963). "Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the ... Congress".

- ^ "Recipients | The Laetare Medal". University of Notre Dame. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- ^ Farley Dies – Jun 10, 1976 – NBC – TV news: Vanderbilt Television News Archive. Tvnews.vanderbilt.edu (June 10, 1976). Retrieved on July 26, 2013.

- ^ 1952 Presidential Election Race: Eisenhower v Stevenson – Video Dailymotion. Dailymotion.com (October 1, 2010). Retrieved on July 26, 2013.

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 131

- ^ Schlesinger 1957, p. 440–443

- ^ Scroop 2006, p. 99

- ^ Scroop 2006, pp. 113–115

- ^ Schlesinger 1957, p. 574–575

- ^ Bill Summary & Status – 97th Congress (1981 – 1982) - H.RES.368 – THOMAS (Library of Congress) Archived July 15, 2012, at archive.today. Thomas.loc.gov. Retrieved on July 26, 2013.

Works cited

[edit]- Schlesinger, Arthur Meier (1957). The age of Roosevelt: the politics of upheaval. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 9780618340873.

- Scroop, Daniel (2006). Mr. Democrat : Jim Farley, the New Deal, and the making of modern American politics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472099306.

- Spencer, Thomas T. (1996). ""Old" Democrats and New Deal Politics: Claude G. Bowers, James A. Farley, and the Changing Democratic Party, 1933–1940". Indiana Magazine of History. 92 (1): 26–45. ISSN 0019-6673.

- Young, William H.; Young, Nancy K. (2007). The Great Depression in America: A Cultural Encyclopedia (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 520–522. ISBN 9780313335204.

Further reading

[edit]- Sheppard, Si (October 14, 2014). The Buying of the Presidency? Franklin D. Roosevelt, the New Deal, and the Election of 1936. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-3106-5.

Primary sources

[edit]- Farley, James A. (1938). Behind the ballots; the personal history of a politician. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co.

- Farley, James A. (1948). Jim Farley's story; the Roosevelt years : Farley, James A. (James Aloysius), 1888-1976 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive. New York: Whittlesey House.

- Farley, James A. "What I Believe". The Atlantic. No. June 1959. Retrieved November 10, 2024.

External links

[edit]- James A. Farley at the National Postal Museum website

- USPS James A. Farley Bio.

- An Interview with Farley (1959) on Folkways Records

- James Farley biography at the National Park Service website

- Bill designating Landmark General Post Office the "James A. Farley Building" Archived July 15, 2012, at archive.today

- The short film OPEN MIND Special: March 4, 1933 (1992) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- The short film Longines Chronoscope with James A. Farley (August 25, 1952) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- The short film Longines Chronoscope with James A. Farley (September 15, 1952) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- Newspaper clippings about James Farley in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- 1888 births

- 1976 deaths

- 1940 United States vice-presidential candidates

- 20th-century American politicians

- American autobiographers

- American campaign managers

- American people of Irish descent

- Burials at Gate of Heaven Cemetery (Hawthorne, New York)

- Candidates in the 1940 United States presidential election

- Candidates in the 1944 United States presidential election

- Catholics from New York (state)

- Democratic National Committee chairs

- Franklin D. Roosevelt administration cabinet members

- Laetare Medal recipients

- Democratic Party members of the New York State Assembly

- People from Stony Point, New York

- United States postmasters general

- Writers from New York City

- New York State Athletic Commissioners