2005 Nias–Simeulue earthquake

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2011) |

| |

| UTC time | 2005-03-28 16:09:37 |

|---|---|

| ISC event | 7486110 |

| USGS-ANSS | ComCat |

| Local date | 28 March 2005 |

| Local time | 23:09:37 |

| Magnitude | 8.6 Mw[1] |

| Depth | 30.0 km (18.6 mi)[1] |

| Epicenter | 2°05′N 97°09′E / 2.09°N 97.15°E[1] |

| Fault | Sunda megathrust |

| Type | Megathrust |

| Areas affected | Indonesia |

| Max. intensity | MMI VIII (Severe)[2] |

| Tsunami | 3.0 m (9.8 ft) at Simeulue |

| Landslides | Yes |

| Casualties | 915–1,314 deaths[3] 340–1,146 injured[3] |

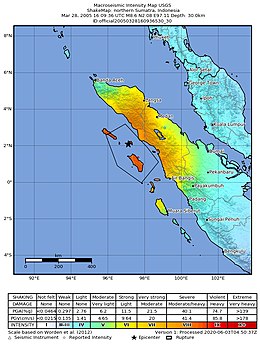

The 2005 Nias–Simeulue earthquake occurred on 28 March off the west coast of northern Sumatra, Indonesia in the subduction zone of the Sunda megathrust. At least 915 people were killed, mostly on the island of Nias. It was among the top 10 most powerful recorded worldwide since 1900,[4] with a magnitude of 8.6 that caused a relatively small tsunami.[5] Damage ranged from hundreds of buildings destroyed in Nias to widespread power outages throughout the island of Sumatra. Following the mainshock, eight major aftershocks occurred ranging from 5.5 to 6.0 magnitudes.

The earthquake occurred at 16:09:37 UTC (23:09:37 local time) on 28 March 2005.[6] The hypocenter was located 30 kilometres (19 mi) below the surface of the Indian Ocean, where subduction is forcing the Indo-Australian plate to the southwest under the Eurasian plate's Sunda edge. The area is 200 kilometres (120 mi) west of Sibolga, Sumatra, or 1,400 kilometres (870 mi) northwest of Jakarta, approximately halfway between the islands of Nias and Simeulue. Effects were felt as far away as Bangkok, Thailand, over 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) away.[7]

Earthquake and damage

[edit]

The earthquake lasted for about two minutes. In the twenty-four hours immediately after the event, there were eight major aftershocks, measuring between 5.5 and 6.0 magnitudes.[8] Despite the proximity of the epicenter to that of the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake, it ruptured a separate segment of the Sunda megathrust and was most likely triggered by stress changes associated with that earlier event.[9] Being situated in the Sunda megathrust subduction zone means that Nias and Simeulue are prone to large earthquakes do to how seismically active the zone is.

On the Indonesian island of Nias, off the coast of Sumatra, hundreds of buildings were destroyed. The death toll on Nias was at least one thousand, with 220 dying in Gunungsitoli, the island's largest town. About 30% of buildings in Gunungsitoli collapsed and it's airstrip was damaged, preventing planes from landing, hampering aid.[10] Nearly half of Gunungsitoli's population (27,000) fled.[10]

The earthquake was strongly felt across the island of Sumatra and caused widespread power outages in the Indonesian city of Banda Aceh, already devastated by the December 2004 tsunami, and prompted thousands to flee their homes and seek higher ground.[11] It was strongly felt along the west coast of Thailand and Malaysia, and in Kuala Lumpur high-rise buildings were evacuated. The earthquake was felt less strongly in the Maldives, India, and Sri Lanka.

The major infrastructure damage to both Nias and Simeulue was their bridges. This was caused by subsidence and lateral spreading displacing the supports of the bridges by 30cm to 100cm.[12] Other damage included destruction to 300 buildings on Nias, and several on Simeulue.[13] Overall, Nias experienced significant damage. Their main electric power generating plant, located at the capitol Gunung Sitoli, experienced shaking thet settled foundations under generators and overturned transformers.[14] It was soon after repaired and power did resume. Ports, bridges, roads, community health clinics, and Nias's main hospital in Gunung Sitoli were all destroyed. In response, IOM (International Organization for Migration) focused on expanding road and bridge repair, putting forth plans to be enacted by 2006 that included construction of 75 temporary schools, homes, and child centers.[15] 11 bridges were repaired and 40 temporary homes constructed.[15] Lots of progress had been made by October 2005, seven months post-event. Plans for permanent schools were underway, 40% of damaged health centers were reconstructed, 25% of mosques and prayer halls were rebuilt, and 80% of fish markets recovered.[16] Damage on Simeulue was less severe, some power lines connecting to Lasikin were damaged, but repaired after a few days, and part of a newly built jetty was submerged, and the terminal, staff residences, and storage building at the airport were destroyed.[14]

Lastly, the reason for so much collapse comes down to the construction of the buildings in Nias and Simeulue. The majority of the buildings that collapsed were non-engineered buildings.[14] There are three categories of non-engingeered buildings, 1-2 story homes of burnt brick or concrete block masonry with sand/cement mortar, 2-4 story homes shop houses of the same materials, and timber buildings. A major issue in Nias and Simeulue was the fact that the shop houses are built by practices of foremen and contractors without the use of structural analysis or drawings.[14] Due to this practice, the building permit system wasn't enforced, leading to no one catching poor material quality or workmanship. 2-4 story shop houses are built as funds are available, meaning it takes months to years for new columns and walls to get built. The issue with this system is that the splicing of the columns is insufficient, resulting in shear failure during shaking.[14] Ultimately, the main issues in the structures of Nias and Simeulue were not building continuously and not upholding building codes.

Afterslips and uplift

[edit]There were eight aftershocks that occurred after the mainshock. These aftershocks occurred due to afterslips along the subduction zone of the Sunda megathrust.[17] This megathrust is located along the northwestern side of the Sumatra island shore. Based on surface deformation, it was interpreted that there were 11 meters of fault-slips in layered elastic spaces under Sumatra.[17] Because of the elastic environment, the converging oceanic and continental plates build energy and are then locked by friction. The continental plate is forced back, and then shortened, causing uplift. The converging plates exceed frictional forces (deformation), causing slip along the fault. After the March 28 earthquake, afterslips continued to occur for 11 months, causing about 8.2 magnitude worth of damage.[17]

Proof of uplift is recorded using cGPS stations, highest level of survival for coral, and coseismic slips.[18] Before the 2005 earthquake, there were already three cGPS sites set up. Three more were set up post quake.[19] These were used to study movement caused by the earthquake, and the Sumatran GPS Array and station were able to record coseismic displacements. Scientists were as well able to study uplift[20] by observing the porites coral heads in relation to tide. Typically a coral's head will grow upwards until their highest corallites are exposed to the atmosphere, killing said corallites and stopping growth.[19] When coseismic slip occurs, lower parts of the coral heads will remain under water and their topmost living tissues will mark a new highest level of survival.[19] Measuring the highest level of survival before the uplift, and measuring the highest level of survival after can provide evidence for how much uplift occurred.

Tsunami

[edit]The earthquake caused great concern around the Indian Ocean that it might trigger a tsunami similar to the massive one generated three months earlier by the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake on 26 December. Evacuations were carried out in coastal regions of Thailand, Malaysia, and Sri Lanka. This earthquake, however, produced a relatively small tsunami. A 3-metre (9.8 ft) tsunami caused moderate damage to the port and airport facilities on Simeulue, and a 2-metre (6.6 ft) tsunami was recorded on the west coast of Nias.[21] Much smaller waves, most detectable only in tide gauge recording systems, were recorded across the Indian Ocean; for example, a 0.21m wave was recorded at Colombo, Sri Lanka[22].

Tsunami warnings were issued by the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center, operated by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and by the government of Thailand. There were initial concerns that a major tsunami could be generated, particularly travelling south from the event's hypocenter.

Portions of Thailand's southern coast were evacuated as a precaution[7], and NOAA advised an evacuation of 965 kilometres (600 mi) of coastline in Sumatra. Evacuations occurred in the northern Malaysian states of Penang and Kedah, as well as the eastern coast of Sri Lanka, where ten people were killed in the confusion of the evacuation[13]. Many of the southern states of India were put on high alert; all of these areas had seen significant damage from December's tsunami. After the detection of a minor tsunami south of the epicenter, the Indian Ocean island states of Mauritius, Madagascar, and the Seychelles issued warnings to their populations. Although tsunami warning systems for the region had been actively discussed before the December 2004 earthquake, none had yet been implemented in the Indian Ocean.

Humanitarian response

[edit]

The United Nations worked with the Indonesian government to take further actions to prevent a possible catastrophe after the strong earthquake. The United States Department of State announced that it will help countries affected by a possible tsunami. The government of India announced aid of US$2 million for victims.[23]

Australia announced it would provide A$1 million in emergency aid and, at the request of the Indonesian Government, dispatched Australian Defence Force medical teams and equipment to Nias. As well as $60 million in humanitarian aid, and reconstruction loans up to $1 billion[24]. The Australian naval ship HMAS Kanimbla, having only recently left Aceh, was redeployed to the region from Singapore. At about 09:30 (UTC) 2 April 2005, one of Kanimbla's two Sea King helicopters, Shark 02, crashed on the island of Nias while taking medical personnel to a village[25]. Nine personnel were killed, and two others sustained injuries but were rescued from the site by the other helicopter. The crash occurred one day before a state visit by President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono to Australia, where he and Prime Minister of Australia John Howard expressed mutual sorrow for their countries' losses. The US Navy responded to this earthquake by deploying the USNS Mercy, a 100-bed hospital ship, off the coast of Nias[26].

In the future

[edit]The likelihood of another event similar to the 2005 Nias-Simeulue earthquake to occur along the Sunda megathrust within the next hundred years is not likely.[27] It takes many centuries to build up enough strain along a fault to cause a slip of great magnitude. Supporting this, there is historical record of a similar earthquake along this fault 140 years ago in 1861, giving events of this magnitude a return interval of around 140 years.[27] With this information, we shouldn't see any major slip at this portion of the megathrust within the next hundred years, but earthquakes are unpredictible so it always possible one occurs in this time frame.

See also

[edit]- 2006 Yogyakarta earthquake

- 2009 Sumatra earthquakes

- 1843 Nias earthquake

- List of megathrust earthquakes

- List of earthquakes in 2005

- List of earthquakes in Indonesia

References

[edit]- ^ a b c ISC (2016), ISC-GEM Global Instrumental Earthquake Catalogue (1900–2012), Version 3.0, International Seismological Centre

- ^ "M 8.6 – northern Sumatra, Indonesia". United States Geological Survey.

- ^ a b PAGER-CAT Earthquake Catalog, Version 2008_06.1, United States Geological Survey, September 4, 2009

- ^ "Largest Earthquakes in the World Since 1900". U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on November 7, 2010. Retrieved November 19, 2024.

- ^ “M 8.6 - 78 Km WSW of Singkil, Indonesia.” Earthquake Hazards Program, United States Geological Survey, earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/official20050328160936530_30/executive#executive. Retrieved 21 Nov. 2024.

- ^ Borrero, J. C.; McAdoo, B.; Jaffe, B.; Dengler, L.; Gelfenbaum, G.; Higman, B.; Hidayat, R.; Moore, A.; Kongko, W.; Lukijanto; Peters, R.; Prasetya, G.; Titov, V.; Yulianto, E. (2011). "Field survey of the March 28, 2005 Nias-Simeulue earthquake and Tsunami". Pure and Applied Geophysics. 168 (6–7): 1075–1088. doi:10.1007/s00024-010-0218-6.

- ^ a b "Southern Thailand evacuated after Indonesian earthquake". Archived from the original on 10 April 2005. Retrieved 28 March 2005.

- ^ "ISC-GEM Catalogue – Introduction". International Seismological Centre. Retrieved 2024-10-17.

- ^ "Poster of the Northern Sumatra Earthquake of 28 March 2005 – Magnitude 8.7". United States Geological Survey. 22 July 2010. Archived from the original on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- ^ a b Betsy, Reed, ed. (2005-03-29), ""Hundreds Pulled from Rubble."", The Guaridan, retrieved 2024-10-17

- ^ Press, MICHAEL CASEY The Associated. "Up to 2,000 Feared Dead In Quake". The Ledger. Retrieved 2024-11-21.

- ^ “The Northern Sumatra Earthquake of March 28, 2005.” The Northern Sumatra Earthquake of March 28, 2005, Aug. 2005, www.eeri.org/lfe/pdf/indonesia_sumatra_northern_report.pdf.

- ^ a b “Today in Earthquake History.” U.S. Geological Survey, 2005, earthquake.usgs.gov/learn/today/index.php?month=3&day=28.

- ^ a b c d e "The Northern Sumatra Earthquake of March 28, 2005" (PDF). EERI. August 2005. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "IOM's response to the 28 Mar 2005 Nias earthquake". Relief Web. 23 March 2006. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Indonesia: Rebuilding a better Aceh and Nias". Relief Web. 26 October 2005. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c Hsu, Ya-Ju; Simons, Mark; Avouac, Jean-Philippe; Galetzka, John; Sieh, Kerry; Chlieh, Mohamed; Natawidjaja, Danny; Prawirodirdjo, Linette; Bock, Yehuda (2006-06-30). "Frictional Afterslip Following the 2005 Nias-Simeulue Earthquake, Sumatra". Science. 312 (5782): 1921–1926. doi:10.1126/science.1126960. hdl:10356/94599. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 16809533.

- ^ "Earthquakes". geology.wisc.edu.

- ^ a b c Briggs, Richard W.; Sieh, Kerry; Meltzner, Aron J.; Natawidjaja, Danny; Galetzka, John; Suwargadi, Bambang; Hsu, Ya-ju; Simons, Mark; Hananto, Nugroho; Suprihanto, Imam; Prayudi, Dudi; Avouac, Jean-Philippe; Prawirodirdjo, Linette; Bock, Yehuda (2006-03-31). "Deformation and Slip Along the Sunda Megathrust in the Great 2005 Nias-Simeulue Earthquake". Science. 311 (5769): 1897–1901. doi:10.1126/science.1122602. hdl:10220/8730. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 16574861.

- ^ "Uplift | Description & Characteristics | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "NCEI Hazard Tsunami Event Information". NOAA. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

- ^ Borrero, J.C., McAdoo, B., Jaffe, B. et al. Field Survey of the March 28, 2005 Nias-Simeulue Earthquake and Tsunami. Pure Appl. Geophys. 168, 1075–1088 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-010-0218-6

- ^ "India announces $2 mn relief for Indonesia". The Times of India. Archived from the original on March 31, 2005. Retrieved 29 March 2005.

- ^ "Humanitarian aid 2004-05". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ “Ran Sea King Accident N16-100 ‘shark 02’ Nias Island Indonesia.” Atsb Crest, www.atsb.gov.au/publications/investigation_reports/2005/aair/aair200502004. Accessed 21 Nov. 2024.

- ^ Negus, Tracy, et al. “Determining Hospital Ship (T-AH) Staffing Requirements ...” Determining Hospital Ship (T-AH) Staffing Requirements for Humanitarian Assistance Missions, Naval Health Research Center, apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA477534.pdf. Accessed 21 Nov. 2024.

- ^ a b Sieh, Kerry. The Sunda Megathrust: Past, Present and Future, tecto.caltech.edu/sumatra/downloads/papers/Snu.pdf. Accessed 17 Nov. 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Boen, T. (2006), "Structural Damage in the March 2005 Nias-Simeulue Earthquake", Earthquake Spectra, 22 (3_suppl): 419–434, Bibcode:2006EarSp..22..419B, doi:10.1193/1.2208147, ISSN 8755-2930, S2CID 110811743

- Borrero, J. C.; McAdoo, B.; Jaffe, B.; Dengler, L.; Gelfenbaum, G.; Higman, B.; Hidayat, R.; Moore, A.; Kongko, W.; Peters, R.; Prasetya, G.; Titov, V.; Yulianto, E. (2010-11-12), "Field Survey of the March 28, 2005 Nias-Simeulue Earthquake and Tsunami", Pure and Applied Geophysics, 168 (6–7): 1075–1088, doi:10.1007/s00024-010-0218-6, ISSN 0033-4553, S2CID 129831201

- Walker, K. T.; Ishii, M.; Shearer, P. M. (2005), "Rupture details of the 28 March 2005 Sumatra Mw8.6 earthquake imaged with teleseismic Pwaves", Geophysical Research Letters, 32 (24): L24303, Bibcode:2005GeoRL..3224303W, doi:10.1029/2005GL024395

External links

[edit]- Lethal quake rattles tsunami zone – BBC News

- Earthquake causes coral reefs to die – CTV News

- Great Earthquake and Tsunami of 28 March 2005 in Sumatra, Indonesia – George Pararas-Carayannis

- The International Seismological Centre has a bibliography and/or authoritative data for this event.

- ReliefWeb's main page for this event.