Howard Carter

Howard Carter | |

|---|---|

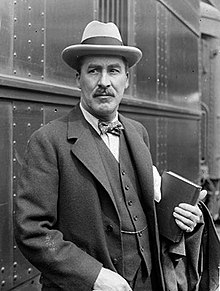

Carter in 1924 | |

| Born | 9 May 1874 Kensington, England |

| Died | 2 March 1939 (aged 64) Kensington, London, England |

| Known for | Discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922 |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Signature | |

Howard Carter (9 May 1874 – 2 March 1939) was a British archaeologist and Egyptologist who discovered the intact tomb of the 18th Dynasty Pharaoh Tutankhamun in November 1922, the best-preserved pharaonic tomb ever found in the Valley of the Kings.

Early life

[edit]Howard Carter was born in Kensington on 9 May 1874,[1] the youngest child (of eleven) of artist and illustrator Samuel John Carter and Martha Joyce Carter (née Sands). His father helped train and develop his artistic talents.[2]

Carter spent much of his childhood with relatives in the Norfolk market town of Swaffham, the birthplace of both his parents.[3][4] His father had previously relocated to London, but after three of the children had died young, Carter, who was a sickly child, was moved to Norfolk and raised for the most part by a nurse in Swaffham.[5]

Receiving only limited formal education at Swaffham, he showed talent as an artist. The nearby mansion of the Amherst family, Didlington Hall, contained a sizable collection of Egyptian antiques, which sparked Carter's interest in that subject. Lady Amherst was impressed by his artistic skills, and in 1891 she prompted the Egypt Exploration Fund (EEF) to send Carter to assist an Amherst family friend, Percy Newberry, in the excavation and recording of Middle Kingdom tombs at Beni Hasan.[6]

Although only 17, Carter was innovative in improving the methods of copying tomb decoration. In 1892, he worked under the tutelage of Flinders Petrie for one season at Amarna, the capital founded by the pharaoh Akhenaten. From 1894 to 1899, he worked with Édouard Naville at Deir el-Bahari, where he recorded the wall reliefs in the temple of Hatshepsut.[7]

In 1899, Carter was appointed Inspector of Monuments for Upper Egypt in the Egyptian Antiquities Service (EAS).[8] Based at Luxor, he oversaw a number of excavations and restorations at nearby Thebes, while in the Valley of the Kings he supervised the systematic exploration of the valley by the American archaeologist Theodore Davis.[7]

In the early 1902, Carter began searching the Valley of the Kings on his own. He initially aimed at the southeast rocky wall of the valley basin. Despite being an inaccessible area, within 3 days he found what he was looking for: stone steps, sepulchral entrance, corridor, sarcophagus chamber, in short, the last home of the fourth Thutmose, carefully stripped (except for a few furnishings and a cart). While digging to find Thutmose IV's final resting place, Howard unearthed an alabaster cup and a small blue scarab with Queen Hatshepsut's name on it.[9]

In February 1903, sixty meters north of the tomb of Thutmose IV, Carter found a stone bearing the ring with the name of Hatshepsut.[9]

In 1904, after a dispute with local people over tomb thefts, he was transferred to the Inspectorate of Lower Egypt.[10] Carter was praised for his improvements in the protection of, and accessibility to, existing excavation sites,[11] and his development of a grid-block system for searching for tombs. The Antiquities Service also provided funding for Carter to head his own excavation projects.

Carter resigned from the Antiquities Service in 1905 after a formal inquiry into what became known as the Saqqara Affair, a violent confrontation that took place on January 8, 1905. between Egyptian site guards and a group of French tourists. Carter sided with the Egyptian personnel, refusing to apologise when the French authorities made an official complaint.[12] Moving back to Luxor, Carter was without formal employment for nearly three years. He made a living by painting and selling watercolours to tourists and, in 1906, acting as a freelance draughtsman for Theodore Davis.[13]

Tutankhamun's tomb

[edit]

In 1907, he began work for Lord Carnarvon, who employed him to supervise the excavation of nobles' tombs in Deir el-Bahari, near Thebes.[14] Gaston Maspero, head of the Egyptian Antiquities Service, had recommended Carter to Carnarvon as he knew he would apply modern archaeological methods and systems of recording.[15] Carter soon developed a good working relationship with his patron, with Lady Burghclere, Carnarvon's sister, observing that "for the next sixteen years the two men worked together with varying fortune, yet ever united not more by their common aim than by their mutual regard and affection".[16]

In 1914, Lord Carnarvon received the concession to dig in the Valley of the Kings.[17] Carter led the work, undertaking a systematic search for any tombs missed by previous expeditions, in particular that of the Pharaoh Tutankhamun. However, excavations were soon interrupted by the First World War, Carter spending the war years working for the British Government as a diplomatic courier and translator. He enthusiastically resumed his excavation work towards the end of 1917.[17]

By 1922, Lord Carnarvon had become dissatisfied with the lack of results after several years of finding little. After considering withdrawing his funding, Carnarvon agreed, after a discussion with Carter, that he would fund one more season of work in the Valley of the Kings.[18]

Carter returned to the Valley of Kings, and investigated a line of huts that he had abandoned a few seasons earlier. The crew cleared the huts and rock debris beneath. On 4 November 1922, a worker uncovered a step in the rock. According to Carter's published account the workmen discovered the step while digging beneath the remains of the huts; other accounts attribute the discovery to a boy digging outside the assigned work area.[19][Note 1] Carter had the steps partially dug out until the top of a mud-plastered doorway was found. The doorway was stamped with indistinct cartouches (oval seals with hieroglyphic writing). Carter ordered the staircase to be refilled, and sent a telegram to Carnarvon, who arrived from England two and a half weeks later on 23 November, accompanied by his daughter Lady Evelyn Herbert.[23]

On 24 November 1922, the full extent of the stairway was cleared and a seal containing Tutankhamun's cartouche found on the outer doorway. This door was removed and the rubble-filled corridor behind cleared, revealing the door of the tomb itself.[24] On 26 November, Carter, with Carnarvon, Lady Evelyn and assistant Arthur Callender in attendance, made a "tiny breach in the top left-hand corner" of the doorway, using a chisel that his grandmother had given him for his 17th birthday. He was able to peer in by the light of a candle and see that many of the gold and ebony treasures were still in place. He did not yet know whether it was "a tomb or merely an old cache", but he did see a promising sealed doorway between two sentinel statues. Carnarvon asked, "Can you see anything?" Carter replied: "Yes, wonderful things!"[25] Carter had, in fact, discovered Tutankhamun's tomb (subsequently designated KV62).[26] The tomb was then secured, to be entered in the presence of an official of the Egyptian Department of Antiquities the next day.[27] However that night, Carter, Carnarvon, Lady Evelyn and Callender apparently made an unauthorised visit, becoming the first people in modern times to enter the tomb.[28][29][30] Some sources suggest that the group also entered the inner burial chamber.[31] In this account, a small hole was found in the chamber's sealed doorway and Carter, Carnarvon and Lady Evelyn crawled through.[30]

The next morning, 27 November, saw an inspection of the tomb in the presence of an Egyptian official. Callender rigged up electric lighting, illuminating a vast haul of items, including gilded couches, chests, thrones, and shrines. They also saw evidence of two further chambers, including the sealed doorway to the inner burial chamber, guarded by two life-size statues of Tutankhamun.[32] In spite of evidence of break-ins in ancient times, the tomb was virtually intact, and would ultimately be found to contain over 5,000 items.

On 29 November the tomb was officially opened in the presence of a number of invited dignitaries and Egyptian officials.[33]

Realising the size and scope of the task ahead, Carter sought help from Albert Lythgoe of the Metropolitan Museum's excavation team, working nearby, who readily agreed to lend a number of his staff, including Arthur Mace and archaeological photographer Harry Burton,[34] while the Egyptian government loaned analytical chemist Alfred Lucas.[35] The next several months were spent cataloguing and conserving the contents of the antechamber under the "often stressful" supervision of Pierre Lacau, director general of the Department of Antiquities.[36] On 16 February 1923, Carter opened the sealed doorway and confirmed it led to a burial chamber, containing the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun. The tomb was considered the best preserved and most intact pharaonic tomb ever found in the Valley of the Kings, and the discovery was eagerly covered by the world's press. However, much to the annoyance of other newspapers, Lord Carnarvon sold exclusive reporting rights to The Times. Only Arthur Merton of that paper was allowed on the scene, and his vivid descriptions helped to establish Carter's reputation with the British public.[37]

Towards the end of February 1923, a rift between Lord Carnarvon and Carter, probably caused by a disagreement on how to manage the supervising Egyptian authorities, temporarily halted the excavation. Work recommenced in early March after Lord Carnarvon apologised to Carter.[38] Later that month Lord Carnarvon contracted blood poisoning while staying in Luxor near the tomb site. He died in Cairo on 5 April 1923.[39] Lady Carnarvon retained her late husband's concession in the Valley of the Kings, allowing Carter to continue his work.

Carter's meticulous assessing and cataloguing of the thousands of objects in the tomb took nearly ten years, most being moved to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. There were several breaks in the work, including one lasting nearly a year in 1924–25, caused by a dispute over what Carter saw as excessive control of the excavation by the Egyptian Antiquities Service. The Egyptian authorities eventually agreed that Carter should complete the tomb's clearance.[40] This continued until 1929, with some final work lasting until February 1932.[41]

Despite the significance of his archaeological find, Carter received no honour from the British government. However, in 1926, he received the Order of the Nile, third class, from King Fuad I of Egypt.[42] He was also awarded an honorary degree of Doctor of Science by Yale University and honorary membership in the Real Academia de la Historia of Madrid, Spain.[43]

Carter wrote a number of books on Egyptology during his career,[44] including Five Years' Exploration at Thebes, co-written with Lord Carnarvon in 1912, describing their early excavations,[45] and a three-volume popular account of the discovery and excavation of Tutankhamun's tomb.[46] He also delivered a series of illustrated lectures on the excavation, including a 1924 tour of Britain, France, Spain and the United States.[47] Those in New York and other US cities were attended by large and enthusiastic audiences, sparking American Egyptomania,[48] with President Coolidge requesting a private lecture.[49]

In 2022, a 1934 letter to Carter from Alan Gardiner came to light, accusing him of stealing from Tutankhamun's tomb. Carter had given Gardiner an amulet and assured him it had not come from the tomb, but Reginald Engelbach, director of the Egyptian Museum, later confirmed its match with other samples originating in the tomb. Egyptologist Bob Brier said the letter proved previous rumours, and the contemporary suspicions of Egyptian authorities, that Carter had been siphoning treasures for himself.[50]

Personal life

[edit]Carter could be awkward in company, particularly with those of a higher social standing.[51] Often abrasive, he admitted to having a hot temper,[52] which often aggravated disputes, including the 1905 Saqqara Affair and the 1924–25 dispute with Egyptian authorities.

The suggestion that Carter had an affair with Lady Evelyn Herbert,[53] the daughter of the 5th Earl of Carnarvon, was later rejected by Lady Evelyn herself, who told her daughter Patricia that "at first I was in awe of him, later I was rather frightened of him", resenting Carter's "determination" to come between her and her father.[54] More recently, the 8th Earl dismissed the idea, describing Carter as a "stoical loner".[55] Harold Plenderleith, a former associate of Carter's at the British Museum, was quoted as saying that he knew "something about Carter that was not fit to disclose", which some have interpreted as meaning that Plenderleith believed that Carter was homosexual.[56] An Egyptian guide who knew Carter claimed that his tastes extended to "both boys and the occasional 'dancing girl'"[57] There is, however, no evidence that Carter enjoyed any close relationships throughout his life,[58] and he never married nor had children.[48]

Later life

[edit]

After the clearance of the tomb had been completed in 1932 Carter retired from excavation work. He continued to live in his house near Luxor in winter and retained a flat in London but, as interest in Tutankhamun declined, he lived a fairly isolated existence with few close friends.[59]

He had acted as a part-time dealer for both collectors and museums for a number of years.[60] He continued in this role, including acting for the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Death

[edit]Carter died from Hodgkin's disease aged 64 at his London flat at 49 Albert Court, next to the Royal Albert Hall, on 2 March 1939.[61][62][63][64] He was buried in Putney Vale Cemetery in London on 6 March, nine people attending his funeral.[65]

His love for Egypt remained strong; the epitaph on his gravestone reads: "May your spirit live, may you spend millions of years, you who love Thebes, sitting with your face to the north wind, your eyes beholding happiness", a quotation taken from the Wishing Cup of Tutankhamun,[66] and "O night, spread thy wings over me as the imperishable stars".[67]

Probate was granted on 5 July 1939 to Egyptologist Henry Burton and to publisher Bruce Sterling Ingram. Carter is described as Howard Carter of Luxor, Upper Egypt, Africa, and of 49 Albert Court, Kensington Grove, Kensington, London. His estate was valued at £2,002 (equivalent to £156,781 in 2023). The second grant of Probate was issued in Cairo on 1 September 1939.[68] In his role as executor, Burton identified at least 18 items in Carter's antiquities collection that had been taken from Tutankhamun's tomb without authorisation. As this was a sensitive matter that could affect Anglo-Egyptian relations, Burton sought wider advice, finally recommending that the items be discreetly presented or sold to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, with most eventually going either there or to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.[69] The Metropolitan Museum items were later returned to Egypt.[70]

Selected publications

[edit]- The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamen (1923) (written together with A. C. Mace)

- The Tomb of Tutankhamun: Volume I – Search, Discovery and Clearance of the Antechamber (1923) (written together with A. C. Mace)

- The Tomb of Tutankhamun: Volume II – Burial Chamber & Mummy (1927)

- The Tomb of Tutankhamun: Volume III – Treasury & Annex (1933)

In popular culture

[edit]Carter's discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb revived popular interest in Ancient Egypt – 'Egyptomania' – and created "Tutmania", which influenced popular song and fashion.[71] Carter used this heightened interest to promote his books on the discovery and his lecture tours in Britain, America and Europe.[47] While interest had waned by the mid-1930s,[72] from the early 1970s touring exhibitions of the tomb's artefacts led to a sustained rise in popularity. This has been reflected in TV dramas, films and books, with Carter's quest and discovery of the tomb portrayed with varying levels of accuracy.[73]

One common element in popular representations of the excavation is the idea of a 'curse'. Carter consistently dismissed the suggestion as 'tommy-rot', commenting that "the sentiment of the Egyptologist ... is not one of fear, but of respect and awe ... entirely opposed to foolish superstitions".[74]

Dramas

[edit]Carter has been portrayed or referred to in many film, television and radio productions:[75]

- In the BBC Radio play The Tomb of Tutankhamen, written by Leonard Cottrell and first broadcast in 1949, he is voiced by Jack Hawkins.[76]

- In the Columbia Pictures Television film The Curse of King Tut's Tomb (1980), he is portrayed by Robin Ellis.

- In the 1981 film Sphinx, he is portrayed by Mark Kingston.

- In George Lucas's TV films Young Indiana Jones and the Curse of the Jackal (1992) and Young Indiana Jones and the Treasure of the Peacock's Eye (1995), he is portrayed by Pip Torrens.

- In the IMAX documentary Mysteries of Egypt (1998), he is portrayed by Timothy Davies.

- In the made-for-TV film The Tutankhamun Conspiracy (2001), he is portrayed by Giles Watling.

- In an episode of 2005 BBC docudrama Egypt, he is portrayed by Stuart Graham.

- He was portrayed in the 2008 Big Finish Radio Drama Forty-five, a title in the Doctor Who range, voiced by Benedict Cumberbatch.[77]

- As the main character in 2016 ITV miniseries Tutankhamun, portrayed by Max Irons.

Literature

[edit]- He is referenced in Hergé's volume 13 of The Adventures of Tintin: The Seven Crystal Balls (1948).[78]

- He is parodied in the 1979 book Motel of the Mysteries by David Macaulay, with a character in the book named Howard Carson.[79]

- He is a key character in Christian Jacq's 1992 book The Tutankhamun Affair.[80]

- James Patterson and Martin Dugard's 2010 book The Murder of King Tut focuses on Carter's search for King Tut's tomb.[81]

- He appears as a main character in Muhammad Al-Mansi Qindeel's 2010 novel A Cloudy Day on the West Side.[82]

- In Laura Lee Guhrke's 2011 historical romance novel Wedding of the Season, Carter's telegram to the fictional British Egyptologist, the Duke of Sunderland, reports discovering "steps to a new tomb" and creates a climactic conflict.[83]

- He is referenced in Sally Beauman's 2014 novel The Visitors, a re-creation of the hunt for Tutankhamun's tomb in Egypt's Valley of the Kings.[84]

- He is a main character in Philipp Vandenberg's 2001 German-language book Der König von Luxor (The King Of Luxor).[85]

- He is a recurring figure in the 1975–2010 Amelia Peabody series, written by Barbara Mertz under the pseudonym Elizabeth Peters. He appears in many of the books, and numbers among the Emersons' circle of friends. In The Ape Who Guards the Balance, for example, he joins them for Christmas dinner shortly after his loss of work for Theodore Davis and his resignation related to the Saqqara Affair, mentioned above.[86]

- Emma Carroll's 2018 novel Secrets of a Sun King depicts Carter as the primary antagonist in a fictional retelling of the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb. A group of children, in possession of a mysterious jar, seek to return it to its original resting place following a series of troubling consequences.[87]

Other

[edit]- A paraphrased extract from Carter's diary of 26 November 1922 is used as the plaintext for Part 3 of the encrypted Kryptos sculpture at the CIA Headquarters in Langley, Virginia.[88]

- On 9 May 2012, Google commemorated Carter's 138th birthday with a Google doodle.[89]

- In 2019, the great-niece of Howard Carter opened a bistro in the town of Swaffham, the town in which Carter spent most of his childhood. The bistro has a collection of Egyptian artefacts and a collection of Carter's work, it also bears the name of Carter's discovery, Tutankhamun.[90]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Karl Kitchen, a reporter for the Boston Globe, wrote in 1924 that a boy named Mohamed Gorgar had found the step; he interviewed Gorgar, who did not say whether the story was true.[20] Lee Keedick, the organiser of Carter's American lecture tour, said Carter attributed the discovery to an unnamed boy carrying water for the workmen.[21] Many recent accounts, such as the 2018 book Tutankhamun: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh by the Egyptologist Zahi Hawass, identify the water-boy as Hussein Abd el-Rassul, a member of a prominent local family. Hawass says he heard this story from el-Rassul in person. Another Egyptologist, Christina Riggs, suggests the story may instead be a conflation of Keedick's account, which was widely publicised by the 1978 book Tutankhamun: The Untold Story by Thomas Hoving, with el-Rassul's long-standing claim to have been the boy who was photographed wearing one of Tutankhamun's pectorals in 1926.[22]

References

[edit]- ^ "Carter, Howard (1874–1939), artist and archaeologist". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32312. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Retrieved 8 November 2022. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Newberry 1939, p. 67.

- ^ Swaffham history Archived 24 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ "The Carter Centenary Gallery". www.swaffhammuseum.co.uk. Retrieved 20 May 2012.[title missing]

- ^ Ingram, Simon (17 October 2022). "Unmasking Howard Carter – the man who found Tutankhamun". National Geographic. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Winstone 2006, pp. 12–15.

- ^ a b Newberry 1939, p. 68.

- ^ Winstone 2006, p. 66.

- ^ a b Pharaoh (13 March 2023). "The incredible life of Howard Carter and the discovery of the Tutankhamun tomb". Neperos.com.

- ^ Winstone 2006, p. 87.

- ^ Ford 1995, p. 19.

- ^ Winstone 2006, pp. 88–92.

- ^ Winstone 2006, pp. 93–95.

- ^ Winstone 2006, p. 95.

- ^ David, Elisabeth (1999). Gaston Maspero 1846–1916: le gentleman égyptologue. Paris: Pygmalion; Gérard Watelet. ISBN 2-85704-565-4.

- ^ Carter & Mace 1923, p. 9.

- ^ a b Price 2007, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Carnarvon, Fiona (2011). Highclere Castle. Highclere Enterprises. p. 59.

- ^ Winstone 2006, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Riggs 2021, p. 297.

- ^ James 2000, p. 255.

- ^ Riggs 2021, pp. 296–298, 407.

- ^ Carter & Mace 1923, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Winstone 2006, pp. 142–145.

- ^ Reeves & Taylor 1992, p. 141, Lord Carnarvon's description, 10 December 1922.

- ^ "KV 62 (Tutankhamen)". Archived from the original on 12 December 2007. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- ^ Carter & Mace 1923, p. 90.

- ^ Lord Carnarvon, The Times (11 Dec 1922), cited in Winstone, p 154.

- ^ Lucas 1942, pp. 135–147.

- ^ a b Hoving 1978, Chapter 9.

- ^ That the group entered the burial chamber is supported by Lucas and Hoving, but dismissed by Carnarvon in The Times, 11 December 1922.

- ^ Carter & Mace 1923, pp. 101–104.

- ^ Winstone 2006, p. 155.

- ^ Ridley, Ronald T. The Dean of Archaeological Photographers: Harry Burton. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 99, 2013. California: SAGE Publishing. pp. 124–126.

- ^ Winstone 2006, p. 297.

- ^ Winstone 2006, p. 134 and passim.

- ^ Winstone 2006, p. 179.

- ^ Price 2007, pp. 130–131.

- ^ "Report of Carnarvon's death". The New York Times. 5 April 1923. Retrieved 12 August 2008.

- ^ Price 2007, pp. 132–134.

- ^ Winstone 2006, pp. 355–356.

- ^ The Scotsman, Saturday 27 March 1926, page 8.

- ^ "Howard Carter, 64, Egyptologist, Dies". The New York Times. 3 March 1939. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ "Howard Carter, 64, Egyptologist, Dies". Goodreads. 3 March 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ Carnarvon, Earl of; Carter, Howard (1912). Five Years' Exploration at Thebes. OCLC 474563606.

- ^ Howard Carter, The Tomb of Tut.Ankh.Amen, 3 volumes.

- ^ a b Cross 2006, p. 92.

- ^ a b "Howard Carter". .historyonthenet.com. 22 July 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ^ Winstone 2006, p. 250.

- ^ Alberge, Dalya (13 August 2022). "Howard Carter stole Tutankhamun's treasure, new evidence suggests". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Winstone 2006, p. 53.

- ^ Winstone 2006, p. 88.

- ^ Hoving 1978, p. 222.

- ^ Winstone 2006, p. 321.

- ^ Furness, Hannah (14 October 2016). "Row over Tutankhamun's tomb affair as ITV drama brings discovery to life". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ Oddy, Andrew (18 October 2016). "An inconvenient crush in King Tut's tomb". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ Paul William Roberts, River In The Desert: modern travels in ancient Egypt, Random House, 1993, p. 102.

- ^ James 2000, p. 463.

- ^ Winstone 2006, pp. 322–325.

- ^ Winstone 2006, p. 133.

- ^ James 2000, pp. 454–455.

- ^ "Howard Carter, 64, Egyptologist, Dies". The New York Times.

- ^ "From The Guardian archives – Egyptologist Howard Carter dies". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ Reeves & Taylor 1992, p. 180.

- ^ Winstone 2006, pp. 326–327.

- ^ Reeves & Taylor 1992, p. 188.

- ^ cf the prayer to the Goddess Nut found on the lids of New Kingdom coffins: "O my mother Nut, spread yourself over me, so that I may be placed among the imperishable stars and may never die."Text From Egypt Centre Trail: Reflections Of Women In Ancient Egypt". 2001. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ probatesearch.service.gov.uk Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ Winstone 2006, pp. 328–330.

- ^ Hawass 2018, p. 23.

- ^ Winstone 2006, p. 2.

- ^ Winstone 2006, p. 324.

- ^ Winstone 2006, p. viii.

- ^ Winstone 2006, p. 326.

- ^ "Howard Carter (Character)". IMDb.com. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017.

- ^ "Radio Times, 27 Feb–5 Mar 1949". BBC Genome Project. 3 March 1949. p. 24. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ Doctor Who: Forty-Five

- ^ Hergé (1944). The Seven Crystal Balls. The Adventures of Tintin. Vol. 13. Le Soir. ISBN 2-203-00112-7.

- ^ Motel of the Mysteries, by David Macauley. Archived 15 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ The Tutankhamun Affair Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ^ Patterson, James; Dugard, Martin (2010). The Murder of King Tut. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-0-446-53977-7.

- ^ Book reviews Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- ^ Guhrke, Laura Lee (2011). Wedding of the Season. Avon Books. ISBN 978-0-06-196315-5.

- ^ The Visitors Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ Vandenberg, Philipp (2001). Der König von Luxor. Luebbe Verlagsgruppe. ISBN 978-3404265992.

- ^ Peters, Elizabeth (1998). The Ape Who Guards the Balance (Audiobook ed.). William Morrow.

- ^ Carroll, Emma (2018). Secrets of a Sun King (Paperback ed.). Faber & Faber.

- ^ Redmond, J.; Ensor, D. (19 June 2005). "Cracking the code: Mysterious 'Kryptos' sculpture challenges CIA employees". CNN.

- ^ "Howard Carter's 138th Birthday". Google Doodle. 9 May 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ "Great-niece of man who discovered Tutankhamun's tomb serves up Egyptian food at new restaurant". 26 September 2019.

Sources and further reading

[edit]- Carnarvon, Fiona (2007). Carnarvon & Carter – The story of the two Englishmen who discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun. Highclere Enterprises.[ISBN missing]

- Carter, Howard; Mace, Arthur (1923). The tomb of Tut Ankh Amen, volume 1. London. OCLC 471731240.

- Cross, William (2006). Carnarvon, Carter and Tutankhamun Revisited: The Hidden Truths and Doomed Relationships. The author. ISBN 1-905914-36-9.

- Ford, Barbara (1995). Howard Carter, Searching for King Tut. New York: Freeman & Company. ISBN 0-7167-6587-X.

- Hawass, Zahi (2018). Tutankhamun. Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh. Melcher Media, New York. ISBN 978-1-59591-1001.

- Hoving, Thomas (1978). Tutankhamun: The Untold Story. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0671243050.

- James, T. G. H. (2000). Howard Carter: The Path to Tutankhamun, Second Edition. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-615-7.

- Lucas, Alfred (1942). "Notes on some of the objects from the tomb of Tutankhamun". Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte (41).

- Newberry, P.E (1939). Howard Carter, obituary. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, vol 25, no 1. June 1939. Egypt Exploration Society, London.

- Paine, Michael. Cities of the Dead; fiction (Howard Carter as narrator); copyright by John Curlovich; Charter Books Publishing, 1988 (ISBN 1-55773-009-1)

- Peck, William H. The Discoverer of the Tomb of Tutankhamun and the Detroit Institute of Arts. Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities. Vol. XI, No. 2, March 1981, pp. 65–67

- Price, Bill (2007). Tutankhamun, Egypt's Most Famous Pharaoh. Pocket Essentials, Hertfordshire. ISBN 978-1842432402.

- Reeves, Nicholas; Taylor, John H. (1992). Howard Carter before Tutankhamun. London: British Museum. ISBN 0810931869.

- Riggs, Christina (2021). Treasured: How Tutankhamun Shaped a Century. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-5417-0121-2.

- Vandenberg, Philipp. Der vergessene Pharao: Unternehmen Tut-ench-Amun, grösste Abenteuer der Archäologie. Orbis, 1978 (ISBN 3570031195); translated as The Forgotten Pharaoh: The Discovery of Tutankhamun. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1980 (ISBN 0340246642)

- Wilkinson, Toby (2020). A World Beneath the Sands: Adventurers and Archaeologists in the Golden Age of Egyptology (Hardbook). London: Picador. ISBN 978-1-5098-5870-5.

- Winstone, H.V.F. (2006). Howard Carter and the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun (Rev edn). Barzan, Manchester. ISBN 1-905521-04-9. OCLC 828501310.

External links

[edit]- Works by Howard Carter at Project Gutenberg

- Five Years' Explorations at Thebes

- Schulz, Matthias (15 January 2010). "Did King Tut's Discoverer Steal from the Tomb?". Der Spiegel Online. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- Works by Howard Carter at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Newspaper clippings about Howard Carter in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- 1874 births

- 1939 deaths

- Burials at Putney Vale Cemetery

- Deaths from lymphoma in England

- Deaths from Hodgkin lymphoma

- Archaeologists from London

- Egyptology

- English Egyptologists

- People from Kensington

- 19th-century British archaeologists

- 20th-century British archaeologists

- Tutankhamun

- Valley of the Kings

- 1922 archaeological discoveries

- 1922 in Egypt

- November 1922 events

- British expatriates in Egypt